December 13, 2024

DAMAGED HERITAGE and J. Chester Johnson on Times Square Jumbotron Dec. 21st

In the midst of the last weekend preceding the seasonal holidays, the Times Square Jumbotron in New York City will, on Saturday, December 21st, display and give attention, on its three-story high screen, to the revelatory book, DAMAGED HERITAGE by J. Chester Johnson. The book contrasts the terrible violence surrounding the largely unknown Elaine Race Massacre along the Mississippi River Delta in 1919 with the remarkably poignant, racial reconciliation that occurred a hundred years later between a black woman and a white man, descendants of opposite sides of the Massacre.

To read more about this Jumbotron event, DAMAGED HERITAGE, and J. Chester Johnson, please CLICK HERE.

October 30, 2024

Damaged Heritage by J. Chester Johnson Selected for Library of Congress Shop

Below the following overview, there is a link to the ad for Damaged Heritage by the Library of Congress Shop. Damaged Heritage is shown alongside books by Ralph Ellison and Vernon E. Jordan, Jr.

Overview:

The books chosen for the Library of Congress shop are primarily publications related to the Library's collections, including books highlighting specific exhibits, rare items from their archives, curated collections on particular topics, and sometimes popular titles that align with the Library's historical focus, often published in collaboration with other publishing houses as part of their "Library of Congress Collection Close-Up" series; essentially, books that showcase the diverse and vast holdings of the Library of Congress itself.

Key points about book selection for the Library of Congress Shop:

Focus on Library Collections:

The main focus is on books derived from the Library's extensive collections, including rare books, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and other unique materials.

Curated Themes:

Books are often chosen based on specific themes or exhibits currently featured at the Library.

Co-Publishing Partnerships:

The Library frequently collaborates with external publishers to produce books specifically for their shop.

Accessibility:

While some books may be scholarly in nature, the shop also features titles aimed at a broader audience, providing a range of reading levels.

Digital Availability:

Many books from the Library of Congress Shop are also available in digital formats through the Library's online platform.

You may view the ad for Damaged Heritage in the Library of Congress Shop at this link.

April 23, 2024

Damaged Heritage by J. Chester Johnson: Anti-Racism Text at St. Luke in the Fields

In April of this year, the St. Luke in the Fields anti-racism group began to read and discuss Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation by J. Chester Johnson (Pegasus/Simon & Schuster). It is expected that the author will join the St. Luke’s group in June for an in-depth examination of various parts of the book that have proven especially relevant and important to the Church’s anti-racism group. An Amazon best-seller, Damaged Heritage was also included in a Goodreads’ international, multi-year list of Best Nonfiction Books.

Located in the historic West Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City, St. Luke in the Fields, an Episcopal church, was founded in 1820 and constructed soon thereafter. Known for its exquisite gardens and music among other programs, St. Luke in the Fields has been an iconic institution in the West Village for many generations. It has also been acknowledged as an activist parish for various causes, being, for example, deeply involved over several decades with the LGBTQ+ community. In addition, the Church’s anti-racism group has been engaged in numerous anti-racism efforts, including participation at the diocesan level.

April 4, 2024

J. Chester Johnson’s “Night” Featured by Carnegie Hill Village

NIGHT

It's a night like none

Of the rest: too much too soon,

Too little too late.

The night overflows

Its peace, so I follow fear

Beyond my insight.

Be still and behold

The moments that I fear most

Pass by in disguise.

“Night” is an example of a triple haiku, a new, poetic form that I have used for several years. This form is derivative of the original haiku, which Japanese poets have employed for centuries. I believe I’m the only American poet now working with the triple haiku, but maybe not. American poets – initially, the Imagists, such as Ezra Pound, Amy Lowell, and John Gould Fletcher – began using a single haiku as a standalone poem in the early part of the 20th century. Toward the end of his life, Auden also wrote frequently in the haiku mode, but not as I have formulated it using three haiku in a poem with each haiku being the equivalent of a stanza, and each stanza being based on the normal haiku structure, having three lines with five syllables in the first and last lines and with seven syllables in the middle line.

J. Chester Johnson, CHV member

March 3, 2024

J. Chester Johnson Named To Board of Advisors For Poetry Outreach Center

J. Chester Johnson, poet and nonfiction writer, has been named to the Board of Advisors for CCNY’s Poetry Outreach Center, which encourages poetry activities in New York City and beyond through workshops, an annual poetry festival, contests, and an annual anthology (Poetry in Performance), containing a range of poets – from student to established.

The Center’s best-known event is the Annual Spring Poetry Festival, which began in 1972 and has often been dubbed New York City’s “Woodstock of the Spoken Word”. The 52nd Annual Spring Poetry Festival will be held on May 10, 2024.

The principal poetry organizations located in New York are all involved in various ways with the Festival, which culminates a year-long series of activities meant to encourage the act of writing poetry among the broadest range of people. Over the years, the Festival has attracted approximately 10,000 elementary school children, an equal number of high school students, college students, and unknown and well-known poets.

The list of honored guest poets reads very much like a Who’s Who of American Poetry.

J. Chester Johnson is the author of several books of poetry, including St. Paul’s Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems and Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems.

Poet and critic, Lawrence Joseph, says of Now And Then: “It provides its readers with the same amplitude of intelligence, passion and formal achievement as our great American epics – Melville’s Moby Dick, Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and Ginsberg’s Fall of America.”

Poet and critic, Major Jackson, offers this opinion of St. Paul’s Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems: “Undoubtedly, this is a work headed for literary permanence in our collective ear.” The American Book Review has written about the signature poem of this volume: “Johnson’s ‘St. Paul’s Chapel’ is one of the most widely distributed, lauded, and translated poems of the current century.”

October 8, 2023

Conversation Among Descendants of the Elaine Race Massacre 104 Years Later: Zoom Recording Available

Here is the link to the recordings made on September 30, 2023. You can watch online or download the recordings at any time using the Passcode: Neverforget1#. You will be able to download the following:

--An MP4 Video Recording of the Session in Speaker View

--An MP4 Video Recording of the Session in Gallery View

--An M4A Audio Recording

--Our Conversation In The Chat Room as a Text File.

--The Complete Transcription of our Session as a VTT file. It can be opened as a Text file.

It’s a “vtt” file….a video text file. Open your TEXT application first. Then look for the vtt file and open it. It will open as a TEXT file, and you can SAVE it as a PDF File.

***PLEASE NOTE***

It is BEST to access the recordings on a laptop or desktop computer. There you will be prompted to DOWNLOAD 5 (or 4) FILES. If you’re using your mobile device, you may be limited to download ONLY the Speaker View Video.

Click Here to Access the files and use the passcode below.

Passcode: Neverforget1#

August 12, 2023

J. Chester Johnson Discusses His Poem, “St. Paul’s Chapel”, At Church of the Heavenly Rest (NYC)

On Sunday, August 6th, J. Chester Johnson spoke at the Church’s Forum about his well-known poem, “St. Paul’s Chapel”. To put the poem in context, he described the long, distinguished history of the Chapel, which is the oldest church building in the borough of Manhattan (NYC). After George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States at Broad and Wall Streets when New York City was the nation’s capital in April, 1789, Washington and his government walked to St. Paul’s Chapel where a worship service was held as part of the country’s first inauguration. Washington continued to attend services at the Chapel until the capital would be moved to Philadelphia before ultimately being established in the District of Columbia. In addition, the funeral for James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, was held at the Chapel on July 7, 1831.

To fast forward 170 years, St. Paul’s Chapel survives the terrorists’ attacks against the twin towers of the World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan on September 11, 2001. As the poem describes, “Not a window broken, not a stone dislodged” occurred at the Chapel. As a result of its escape from so much destruction that occurred to neighboring buildings and because of its nearness to the Ground Zero pile, the Chapel became the relief center for the recovery workers during the 8.5 month cleanup at the site. Over 14,000 volunteers from all across the country came to the Chapel to help give not only respite and refreshment to the recovery workers, but also spiritual support; indeed, the Chapel’s efforts on behalf of the workers caused the Chapel to become known as “the spiritual home of Ground Zero”.

Johnson’s poem, combining both the Chapel’s history and the then currency of its 2001-2002 relief center mission in the aftermath of the attacks, became the Chapel’s memento poem card in 2002 and has remained for that purpose in the Chapel for over twenty years with over 1.5 million cards being distributed at the Chapel. In 2017, the poem was characterized by the American Book Review as “one of the most widely distributed, lauded, and translated poems of the current century.” The entirety of the poem appears elsewhere on this website.

Click on the image above to watch Johnson’s presentation on his poem, “St. Paul’s Chapel”, at the Church of the Heavenly Rest.

April 3, 2023

J. Chester Johnson Interviewed by Tavis Smiley

At 2:00PM ET on Wednesday, March 21, Tavis Smiley interviewed J. Chester Johnson for an hour on Johnson’s book, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation. The interview occurred on Tavis Smiley’s national talk radio program at KBLA (1580). Based out of Los Angeles, KBLA is the only Black-owned talk radio station west of the Mississippi and is committed to offer an educated and empowering perspective to all its listeners in Los Angeles and the nation.

Click Here to Listen to the Broadcast On Spotify.

January 25, 2023

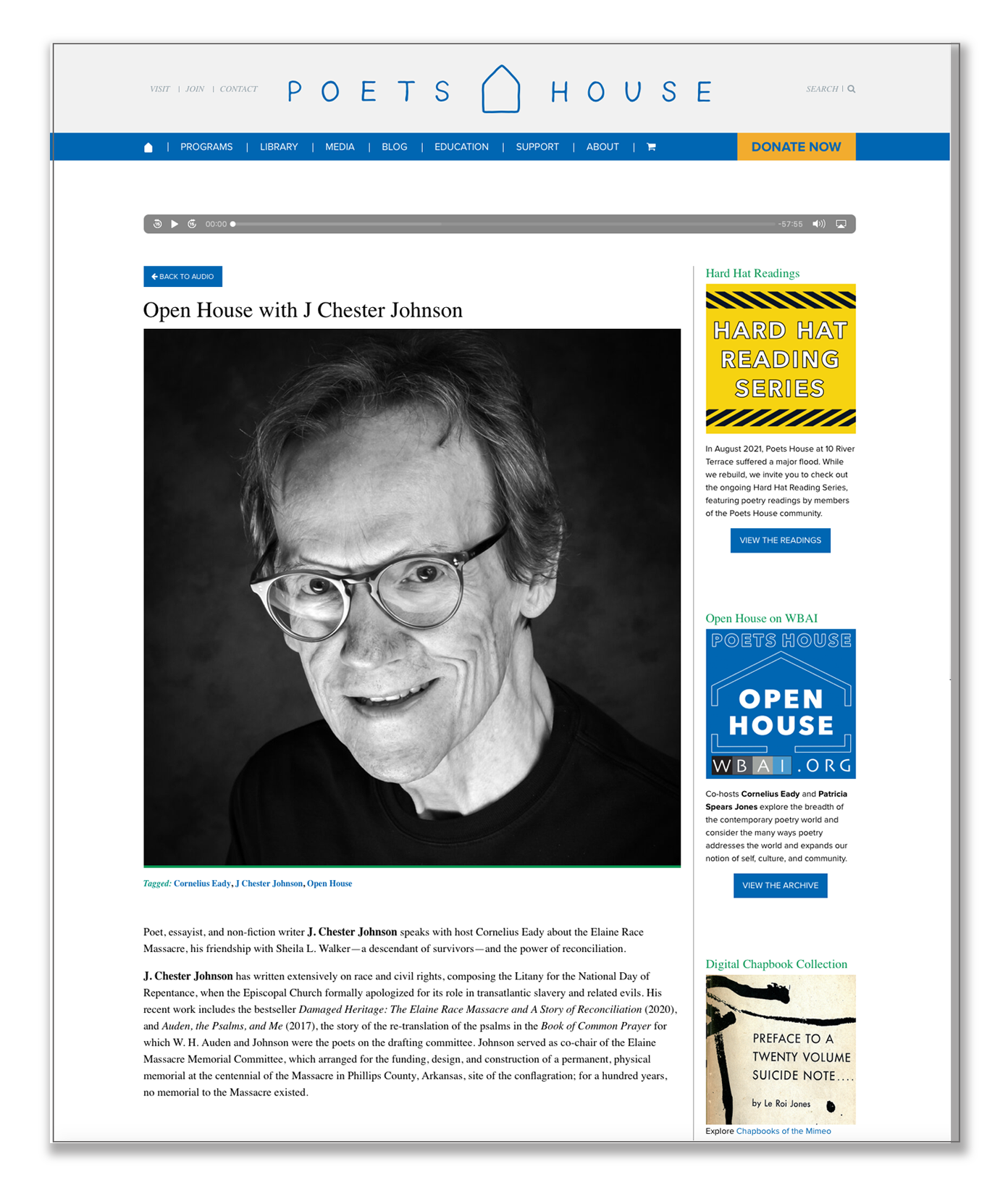

Cornelius Eady’s Interview of J. Chester Johnson for Poets House/WBAI “Open House” Program

For those who missed the interview on WBAI (NYC) Friday night (1/20/2023), you can gain access (regardless of your location) to the entirety of the interview by clicking on the following Poets House link. The principal topics discussed were the Elaine Race Massacre, Chester’s friendship with Sheila Walker – a descendant of survivors, the power of reconciliation, and Chester’s poem, “On Dedicating The Elaine Massacre Memorial”.

For those who missed the interview on WBAI (NYC) Friday night (1/20/2023), you can gain access (regardless of your location) to the entirety of the interview by clicking on the following Poets House link. The principal topics discussed were the Elaine Race Massacre, Chester’s friendship with Sheila Walker – a descendant of survivors, the power of reconciliation, and Chester’s poem, “On Dedicating The Elaine Massacre Memorial”.

CLICK HERE to listen to the recording.

December 20, 2022

NPR Article on Elaine and Tulsa Race Massacres

On Sunday, December 11th, the National Public Radio (NPR) published an in-depth article comparing the Elaine and Tulsa Race Massacres, which are estimated to have caused approximately the same number of deaths. The environment surrounding each massacre was quite different, for one involved the destruction of the country’s Black Wall Street in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, while the other happened in a remote, rural area along the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River Delta to poor Black sharecroppers. The country’s response to the two events has been stark with considerable national attention being paid to Tulsa, but with only a relatively few people in the United States being familiar with the Elaine conflagration. The article attempts to give guidance to the reasons for this remarkable differential in coverage and attention.

On Sunday, December 11th, the National Public Radio (NPR) published an in-depth article comparing the Elaine and Tulsa Race Massacres, which are estimated to have caused approximately the same number of deaths. The environment surrounding each massacre was quite different, for one involved the destruction of the country’s Black Wall Street in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, while the other happened in a remote, rural area along the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River Delta to poor Black sharecroppers. The country’s response to the two events has been stark with considerable national attention being paid to Tulsa, but with only a relatively few people in the United States being familiar with the Elaine conflagration. The article attempts to give guidance to the reasons for this remarkable differential in coverage and attention.

Click Here to Read the Article.

September 24, 2022

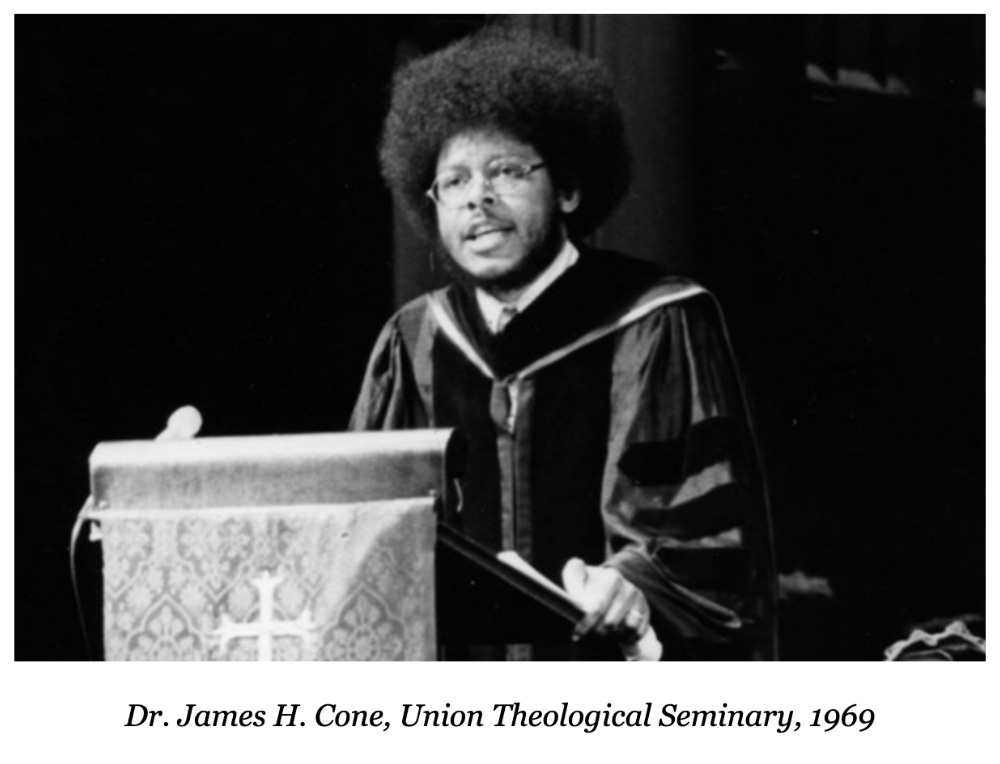

HNN Publishes Article by J. Chester Johnson on Father of Black Liberation Theology

The summer of 2013 proved especially consequential for me, occasioned by a series of four private lunches with Dr. James H. Cone, author of Black Theology & Black Power, a book that has, since its release, carried the distinction as “the founding text of Black liberation theology.” To Cone, long-time distinguished professor at Union Theological Seminary, the gospel of Christianity had been hijacked and distorted by “white, Euro-American values.”

To continue reading on History News Network, please click here.

September 10, 2022

Favorable Review of “Damaged Heritage” in Current Issue of American Book Review

The Spring 2022 issue of American Book Review includes a review of Damaged Heritage by Robert Whitaker. I have received permission to share this article with you.

American Book Review

Volume 43, Number 1, Spring 2022 University of Nebraska Press

Reviewed by:

Robert Whitaker

As the 1619 Project reminds us, our nation's damaged heritage stretches back more than four centuries, to the moment that the first Africans were brought to the New World to labor under the yoke of slavery, and here we are today, still in need of protests that proclaim, "Black Lives Matter," and still hearing of resistance to teaching this history in our schools. Readers of J. Chester Johnson's aptly titled book, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Riot and a Story of Reconciliation, will recognize that although his story is autobiographical, he serves as an Everyman, telling of a need for us all to confront this past, which so infects our present. His deep friendship with Sheila Walker serves a model for moving forward with a shared understanding of history.

This is a book about escaping from the talons of our damaged heritage, so infused with racism, violence, and a societal narrative that turns a blind eye to such facts. Johnson has a particular heritage that haunts him. After his father died when he was not yet two, he spent his preschool years in Little Rock with his grandparents. His grandfather Lonnie doted on him, and some of his earliest memories are of sitting in Lonnie's lap. Yet, years later, he would come to understand that Lonnie had been a member of the Ku Klux Klan, donning the white sheet on many nights, and that he had been a member of the mob that killed Black sharecroppers in Phillips County, Arkansas, in 1919.

In an imaginary letter to Lonnie, Johnson writes: [End Page 85]

"While I have unreservedly written here and accepted that you are part of me, you cannot be in fact and in sum, for consciously and unabashedly, I abhor that part of you who pursued a massacre of blacks, you who could mortify, terrorize, burn, or lynch, and then claim the rightness of it all with an allegiance to the proposition of superiority for a white coterie."

Although it is always difficult to know why one person retains the values of the culture they grew up in while another breaks from those values, there was an early experience in Johnson's life that prepared him for the latter course. In 1949, when his mother moved their family to Monticello, his backyard was adjacent to a field that, on the opposite side, was home to Black families. There, in this no-man's land, they played pick-up games of baseball with young Chester, the only white child, and yet everyone also knew the rules: his Black friends would never be invited into his home, and the opposite was true too.

Those friendships proved fleeting once Chester developed new friends at the all-white elementary school, and that remained true for the rest of his youth. However, upheaval to Arkansas's Jim Crow world came in 1957, when nine Black students integrated the Little Rock High School, with white mobs hurling insults and threats as they entered the school under the protection of federal troops. Johnson's early friendship with Black children prompted him to begin to separate himself-at least in his mind-from those who would countenance such hate.

Chester went off to Harvard, but after the Summer of 1964, when Freedom Riders went to Mississippi to register Black voters, he dropped out and returned to Arkansas. He traveled widely, occasionally sleeping in his car, intent on better understanding the South and its residents. At the end of that journey, he often spoke with an older Black man who lived in the woods outside Monticello, the two of them drinking whiskey together. After earning a degree from the University of Arkansas, he spent the turbulent year of 1969 teaching at a Black school in Monticello and running for mayor. He knocked on every door in town during that effort, which, when accompanied by a Black friend, provided him the opportunity to be with the Black community in their homes. [End Page 86]

He lost that election, having narrowly escaped a beating by the local "peckerwoods" who didn't cotton to his teaching at the local Black school and, having "foresworn being a white Southerner, burdened with its persona from a damaged heritage," he moved to New York City. There he attained professional success as a "public finance specialist," serving as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the US Treasury Department under Jimmy Carter.

In 2008, Johnson was selected by the Episcopal Church to write the Litany of Offense and Apology for a National Day of Repentance, which served as a formal apology by the church for its role in transatlantic slavery. While working on that project, he read Ida B. Wells's account of The Arkansas Race Riot (1920), and this was the moment when his damaged heritage came fully to light.

While there has been a great deal of attention during the past year to the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921, the Elaine Massacre is much less well known, and only in recent years has it entered the history books.

That fall, sharecroppers in the southern part of Phillips County began organizing a union to wage a legal fight for their fair share of the revenue from the cotton crop that year. Late in the evening of September 30th, they were meeting in a roadside church in Hoop Spur, a few miles north of Elaine, when a car pulled up outside and cut its lights. There was an exchange of gunfire, and when the smoke cleared, the church was riddled with bullet holes and a white security agent for the Missouri-Pacific railroad was lying dead in the road next to his Model T. The next morning, posses from Helena descended on the area, shooting sharecroppers hiding in the Govan Slough; next, mobs from outside the county came and began a more indiscriminate killing of Blacks in the area; and finally, Army troops from Little Rock arrived, chasing sharecroppers into the canebrakes and, as white newspapers reported, the rat-a-tattat of their machine guns filled the air.

What Johnson now understood was that the grandfather he adored, who in 1919 was working for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, stationed in nearby McGeHee, had gone to Hoop Spur and participated in the killing of the Black sharecroppers.

His reconciliation with Sheila Walker crossed this vast historical divide. Her great grandmother, Sallie Giles, and her two sons, Albert and Milligan, were in the church the night it was shot up. The next morning, as a Helena [End Page 87] posse descended on their cabin, Albert and Milligan fled to the slough to hide. Albert was shot in the head, the bullet passing through his skull, and fifteen-year-old Milligan was shot in the face. Remarkably, both survived, and then came more white violence for the Giles family: the two were imprisoned for having participated in what white authorities described as a "conspiracy" by Blacks to kill the plantation owners and take over their lands. Albert was condemned to die in the electric chair, but eventually was saved from that fate by the extraordinary legal work of Scipio African us Jones, a case that led to a Supreme Court decision in Moore v. Dempsey that served as a legal foundation for the Civil Rights movement.

Sheila Walker passed earlier this year, and one wishes that there was a biography of her life that could be read alongside Johnson's. Hers is a story of a family that continued to suffer from our unequal society, Walker and her siblings growing up desperately poor in a crowded Chicago apartment. In the 1960s, as a member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Walker participated in protests, sit-ins, and other Civil Rights struggles. While she eventually escaped the poverty of her youth, several of her siblings did not, their lives ransacked by drugs.

Much like Chester Johnson, she never heard anyone speak directly about the Elaine Massacre, although in 1973 her grandmother Annie, while telling of living in Phillips County, began to cry hysterically while describing a night when the Hoop Spur church had been shot up. Something awful had happened to her family, but it wasn't until she read Grif Stockley's 2001 book Blood in Their Eyes and other accounts of the massacre that this history became known to her.

When Chester Johnson and Sheila Walker first spoke, they took pains to come to a common understanding of the history of the Elaine Massacre, which was essential to their subsequent reconciliation. There had long been a white version, which in essence told of a Black riot that had been put down by white authorities with only fifteen to twenty Blacks killed, and there had long been a Black version, which told of a massacre of one hundred or more Blacks, and as they had both read everything they could about the subject, they both agreed that the latter was true.

From there, an extraordinary friendship developed. The two talked regularly on the phone and they spoke together at multiple public events, where [End Page 88] those in the audience could see the affection and respect they had for each other. Sheila Walker was a person of extraordinary grace, who could speak eloquently about Black Liberation and the need for a national reconciliation in this country, and as Johnson relates, it was she who counseled him that he needed to forgive his grandfather Lonnie for what he had done in 1919.

"People aren't bad," she told him. "Circumstances make people do bad things."

Johnson, who has won praise for his books of poetry, is a gifted writer. Damaged Heritage is part memoir, part history, and part essay on racism, all tied together by a story of a friendship that transcended the racial gulf that so regularly plagues our country. Throughout, he reflects on our damaged heritage as a nation and how it remains so difficult for our society to confront this heritage.

This book provides a model for doing so, starting with the teaching and acceptance of a shared narrative of our country's history, and then calling on our better selves to foster a national reconciliation.

Robert Whitaker is the author of On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation (2008).

Copyright© 2022 American Book Review - Permission given to J. Chester Johnson

April 28, 2022

“Damaged Heritage” Placed On Selective Goodreads’ List of Best Nonfiction Books

Damaged Heritage appears on a Goodreads’ multi-year, international list (less than 500 books) for Best Nonfiction Books (alongside The Diary of Anne Frank, Hiroshima, and The Gulag Archipelago, among others). Set forth below is a selective list of various books included on the Goodreads’ list.

1. The Diary of Anne Frank

2. Hiroshima – John Hersey

3. In Cold Blood – Truman Capote

7. Night – Elie Wiesel

39. The Gulag Archipelago – Alexander Solzhenitsyn

128. Massacres In The American West – Larry McMurtry

134. The Great Fire of London – Samuel Pepys

262. Slavery by Another Name – Douglas Blackmon

269. Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee – Dee Brown

348. The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor – Gabriel Garcia Marquez

358. On Lynching – Ida B. Wells-Barnett

387. The Strange Career of Jim Crow – C. Vann Woodward

418. The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War – David Halberstam

420. Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation – J. Chester Johnson

420. Playing With Fire – Lawrence O’Donnell

431. The Oklahoma City Bombing and the Politics of Terror – David Hoffman

433. Battle Cry of Freedom – James M. McPherson

435. The Barbarous Years: Peopling of North America, 1600-1675 – Bernard Bailyn

445. A Hoxton Childhood – A. S. Jasper

April 25, 2022

“Damaged Heritage” Motivates Nationwide Talks on Social Justice and Racial Equity

Message Recently Received From APJMM:

"Damaged Heritage" has motivated APJMM (Arkansas Peace & Justice Memorial Movement) to set up the central Arkansas chapter of Coming to the Table, a national non-profit organization that works to get the descendants of the enslaved and the enslavers to sit down at the table together to talk. And, since March 2020, we have hosted FREE bi-weekly virtual gatherings that have attracted over a thousand people nationwide to participate in talks about social justice and racial equity issues.

Arkansas Peace & Justice Memorial Movement

April 18, 2022

J. Chester Johnson Writes in the ARKANSAS TIMES About Another Arkansas Race Massacre

In late September, 2019, an evocative and dramatic memorial was dedicated in Phillips County, Arkansas to the victims of the Elaine Race Massacre. J. Chester Johnson served as co-chair for this memorial. A conclusion impelled him to acknowledge emphatically and publicly that the Elaine Massacre did not occur in a vacuum, for the long arm of history reached into Phillips County and set in motion a course of unmitigated violence and consumptive death against a vast number of African-Americans. Based on additional research, Johnson discovered another race massacre against African-Americans in Arkansas – the Little River Race Massacre of 1899, an article about which he recently wrote for the ARKANSAS TIMES.

Click Here to read the article by J.Chester Johnson.

April 11, 2022

Video of J. Chester Johnson’s presentation at Johnson House Historic Site (Underground Railroad).

The Johnson House Historic Site is an icon of the Underground Railroad Freedom Movement – not returning one runaway slave to a master, notwithstanding the existence of the heinous Fugitive Act in effect at the time. J. Chester Johnson spoke to an outdoor gathering at the Johnson House on September 17, 2021. Here is an 18-minute video of the event, celebrating Sheila L. Walker, Chester’s partner in racial healing and reconciliation, and featuring his book, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation.

Click here to learn more about Johnson House.

Click on the image below to watch the 18-minute video presentation that honors Sheila L. Walker and features J. Chester Johnson's book, “Damaged Heritage”.

April 10, 2022

Book Review from Green Mountains Review of “Damaged Heritage”

“Death and Hope from ‘The Heart of Darkness’”, book review of Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation by J. Chester Johnson, was authored by Dr. Carol Strong, Professor of Political Science at the University of Arkansas (Monticello), which is located only one county removed from the Elaine Race Massacre.

Read here Dr. Strong’s book review appearing in the Green Mountains Review.

October 20, 2021

Flying Into the Unpredictable: Publishing During a Pandemic

Best American Poetry Blog

Editor’s Note (October 19, 2021):

We checked in with J. Chester Johnson to find out how he’s fared over the course of the last 18 months with the publication of his timely Damaged Heritage.

Click here to read the article on the Best American Poetry web site.

October 4, 2021

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art: Remembering the Elaine Massacre

Here is the piece prepared by Crystal Bridges on the Elaine Race Massacre, including a link to an interview by National Public Radio with J. Chester Johnson, author of Damaged Heritage, and Dr. Kyle Miller, who lost four ancestors in the white attacks and who is executive director of the Arkansas Delta Cultural Center in Phillips County, Arkansas, site of the Massacre.

Click Here to Learn More.

September 15, 2021

Cornelius Eady and J. Chester Johnson Discuss Their 9/11 Poetry On BCR’s Inaugural Poetry Podcast

The Poetry Foundation editors write: “When major parts of our lives seem to change in a flash, we are reminded that poetry can help us to cope with new realities and to assess the unknowns ahead. When we are stepping out into uncharted terrain, alone or together, poetry can capture our emotions. It can share our vulnerabilities and scars, along with our strengths.”

Today. we are sharing the first program of our new podcast co-produced with Chris Brandt -- “Poetry. What is it good for?” For this first episode, we explored the 20-year social and emotional after-tremors of the attack by Saudi Arabian terrorists on the United States through the powerful tool of poetry with J. Chester Johnson and Cornelius Eady.

J. Chester Johnson is a poet and non-fiction writer. He visited Bar Crawl Radio a couple of months ago to talk about his book – “Damaged Heritage” -- on the history and his family’s connection with the 1919 Elaine, Arkansas Massacre, one of many human crimes against humanity in which U. S. White citizens killed over 100 U.S. Black citizens and then prosecuted the survivors for their act of murder.

Though Cornelius Eady, an American poet, focuses on issues of race and society, his verse accomplishes a lot more as indicated in his deeply felt reactions to the 9/11 attack on this country. Cornelius is also a musician whose verse is performed as song by The Cornelius Eady Trio. His poetry is simple and accessible, centering on jazz and blues, family life, violence, and society from a racial and class-based POV.

August 18, 2021

LitHub: J. Chester Johnson Interviewed for ‘Keen On’ Podcast About Damaged Heritage

Hosted by Andrew Keen, Keen On features conversations with some of the world’s leading thinkers and writers about the economic, political, and technological issues being discussed in the news, right now.

Hosted by Andrew Keen, Keen On features conversations with some of the world’s leading thinkers and writers about the economic, political, and technological issues being discussed in the news, right now.

In this episode, Andrew is joined by J. Chester Johnson, the author of Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and a Story of Reconciliation, to discuss a deliberately erased chapter in American history, as well as to offer a blueprint for how our pluralistic society can at last acknowledge—and deal with—damaged heritage.

Click Here for Interview

March 25, 2021

Literary Hub Shares Excerpt From Damaged Heritage by J. Chester Johnson

Explore a Deliberately Erased Chapter in American History

In 2008, poet and essayist J. Chester Johnson was asked to write the Litany of Offense and Apology for the National Day of Repentance when the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils. In his research, he learned about the 1919 Elaine Massacre, in which more than 100 African-American men, women, and children (possibly, hundreds) were killed by white vigilantes and federal troops. Then, digging further, Johnson discovered that his beloved grandfather, who’d raised him during his Arkansas boyhood, had participated in the Massacre.

Damaged Heritage not only describes how Johnson comes to terms with these life-shattering revelations, but it also describes the racial reconciliation he forges with Sheila. L. Walker, descendant of several Massacre victims, who writes the Foreword to the book. It’s a story of guilt, pain, and racial reconciliation that offers lessons for an entire nation grappling with a history of racism.

FROM THE BOOK: Across the sweeping canvas of American history, two markers, inherited and ineluctable, from the Elaine Race Massacre of 1919 in Phillips County, Arkansas, invite a degree of attention yet to be fully received from the country’s public consciousness. First, the sheer number of persons who died in the Massacre—more particularly, the countless African-Americans who perished—would certainly cause this massacre to be judged one of the deadliest racial conflicts, perhaps the deadliest racial conflagration, in the history of the nation.

READ THE FULL EXCERPT

An illuminating journey to racial reconciliation experienced by two Americans—one black and one white.

The 1919 Elaine Race Massacre, arguably the worst in our country's history, has been widely unknown for the better part of a century, thanks to the whitewashing of history. In 2008, Johnson was asked to write the Litany of Offense and Apology for a National Day of Repentance, where the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils.

In his research, Johnson came upon a treatise by historian and anti-lynching advocate Ida B. Wells on the Elaine Massacre, where more than a hundred and possibly hundreds of African-American men, women, and children perished at the hands of white posses, vigilantes, and federal troops in rural Phillips County, Arkansas.

As he worked, Johnson would discover that his beloved grandfather had participated in the Massacre. The discovery shook him to his core. Determined to find some way to acknowledge and reconcile this terrible truth, Chester would eventually meet Sheila L. Walker, a descendant of African-American victims of the Massacre. She herself had also been on her own migration in family history that led straight to the Elaine Race Massacre. Together, she and Johnson committed themselves to a journey of racial reconciliation and abiding friendship.

BUY THE BOOK

December 3, 2020

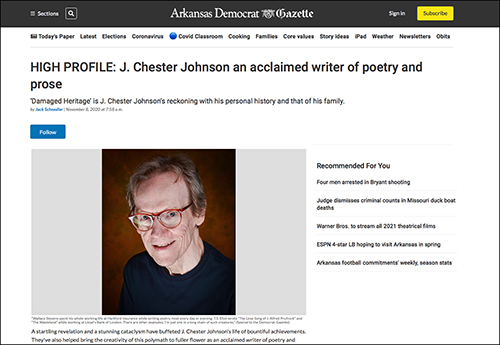

‘Damaged Heritage’ Is Personal Reckoning For J. Chester Johnson

The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette wrote a high profile, 2,000 word plus article on the writer and poet, J. Chester Johnson, that was published on Sunday, November 8, 2020. Below is a link to the contents of that article in its entirety.

Click Here.

October 16, 2020

Damaged Heritage: Presentation & Discussion with J. Chester Johnson – The Center for Reconciliation

On October 8th, 2020, The Center for Reconciliation was excited to welcome author J. Chester Johnson for a virtual presentation on and discussion of his recent publication, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation.

An illuminating journey to racial reconciliation experienced by two Americans – one Black and one white – Damaged Heritage examines how white Americans’ excessive reverence of the past permits the damaged heritage of racism to be transferred from generation to generation. It also offers a blueprint for how our society can at last acknowledge – and repudiate – damaged heritage and begin a path toward true healing.

A well-known poet, essayist, and translator from the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River Delta, Johnson has written extensively on race and civil rights, including composing the Litany for the Episcopal Church’s National Day of Repentance for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils.

View a video of the presentation below.

Hosted by The Center for Reconciliation

July 23, 2020

J. Chester Johnson Presents Damaged Heritage to the Washington National Cathedral, Sunday, June 28th

A world-wide audience heard J. Chester Johnson discuss his newest book, Damaged Heritage, through the National Cathedral on Sunday afternoon, June 28th. Utilizing the internet, the Cathedral brought together attendees from Europe and Africa, in addition to the United States, to experience Johnson’s comments about Damaged Heritage, published on May 5th by Pegasus (distributed by Simon & Schuster). The Elaine Race Massacre, possibly the most significant racial attack against African-Americans in our country’s history, occurred in the early fall of 1919 along the Mississippi River Delta in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. This Massacre serves as the backdrop for Johnson’s memoir that recounts the effects of having grown up in southeast Arkansas, one county removed from the site of the Massacre, and an especially racist region of the country. A large part of the book reflects Johnson’s own views on the causation of generational repetition of American white racism. In addition, the book, as recounted by Johnson, describes a journey of racial reconciliation between himself and Sheila L. Walker, who wrote the Foreword to Damaged Heritage and who had several ancestors that were victims of the Massacre. For the last six years, Sheila Walker and Johnson have pursued a course that has led to an abiding friendship, though the two came from the two sides of the Elaine conflagration. He discussed with the audience how that friendship has now included the respective spouses and children in the process of achieving reconciliation.

June 19, 2020

Damaged Heritage: A Conversation

On Sunday, June 14th, at 2:30PM, a large number of attendees participated in a Zoom program that was focused on the new book, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation by J. Chester Johnson. The program was sponsored by Trinity Church Wall Street and consisted of a presentation by the author; a discussion on the book by the author and Dr. Catherine Meeks, Executive Director of the Absalom Jones Episcopal Center for Racial Healing; and a general question and answer session that involved participation by the attendees for this Zoom program.

Click here for the entirety of the program.

June 18, 2020

Elaine Race Massacre: Truth Before Reconciliation by James Melchiorre, Trinity Church Wall Street

Poet and author Chester Johnson knew his mom’s dad as a loving grandfather. Johnson now knows that grandfather, Lonnie Birch, joined in a massacre that killed more than one hundred African Americans in 1919 near and around the town of Elaine in southeast Arkansas. The violence began after black sharecroppers, having returned from military service in World War I, formed a union to negotiate for higher cotton prices, and had called a meeting inside a local church.

“The deputy sheriff and a security agent for the Missouri Pacific Railroad started shooting in the church to break up the meeting, The union had hired guards outside and the guards shot back,” Johnson said. “A lot of white planters felt this was the beginning of a black insurrection so they sent out posses the next morning.” Federal troops also arrived, adding to the death toll which fell, not exclusively but overwhelmingly, on the black sharecroppers.

Sheila Walker is a native Arkansan, who learned about the massacre as a child even though she, like Chester Johnson, was born more than two decades after it occurred.

“I first heard about this story through my grandmother. She would always start talking about it and then just start crying, hysterical, post traumatic stress. My uncle Albert, I think he was shot twice, once in the arm and then in the neck. Uncle Jim, he was shot in the face during the massacre.”

“Race riot” was the term used in local accounts, and that's how Johnson heard it described during his teenage years by his mother, who added a family connection.

“My mother on several occasions made reference to the fact that Lonnie, my maternal grandfather who cared for me the first few years of my life, had participated in what she called a well-known race riot where many African Americans were killed." Johnson says it was also widely known within his family that Lonnie Birch was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Although Johnson had heard, as a teenager, his mother’s vague reference to his grandfather's participation, he never truly connected the dots until fifty years later when he read an account of the violence at Elaine written by Ida B. Wells, the journalist and anti-lynching activist.

“I’m still struggling with it. He is bifurcated. Basically he rescued me when I was one after my father died. I mean we were incredibly close when I was living with him, but then I’ve got this image of this gunman who is participating in this terrible massacre.”

The realization led to Johnson’s book “Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and a Story of Reconciliation.” The book details the violence of Elaine, the use of torture to force the African American sharecroppers into “confessing” the white planters’ version of the event. Sheila Walker’s Uncle Albert was among those arrested, convicted, and sentenced to death. The planned executions never happened because of what is considered a landmark Supreme Court case Moore v Dempsey.

Six years ago, their family connections, on opposite sides, to the massacre led to a meeting, and a friendship, between Sheila Walker and Chester Johnson. The two were brought together by a historian who shared with Walker an article Johnson had written about Elaine.

“When I saw how Chester had framed it as a massacre, not only framing it but actually calling it out for what it was, I read the article. For Chester to even come forward, it’s an act on his part of reaching out, and it’s an act on his part of the acknowledgement,” Walker said.

“It was truth that was put first, and that’s the way in which Sheila and I have related to this. I mean Lonnie’s my grandfather. I didn’t participate in the massacre, but I inherited this event and his participation in it. What I do with it is I deal with it. If I don’t deal with it, then I’m basically foisting it forward with sort of the same mythologies that existed in 1919,” Johnson said.

The friendship between Sheila Walker and Chester Johnson led to more than a book. It also led to a mission. Both Walker and Johnson wanted to publicly memorialize the violent events of 1919 in Elaine.

They achieved success on September 29, 2019, a century from the start of the violence, when they both attended the dedication of the Elaine Massacre Memorial in Helena, Arkansas.

“The memorial. Oh, my God, the feeling was just, for me, it was something that will start a conversation. If I was a stranger and I saw that I would want to know more. If I’m interested in any type of social justice I would want to know more,” Sheila Walker said.

Even as she celebrates the success she and Chester Johnson achieved in the public recognition of the massacre, Sheila Walker offers a reminder that truth-telling about the history of white supremacy, systemic racism, and violence, while indispensable to creating change, is not the end of the story. Walker says that's a reality dramatized by what she saw when she traveled to southeast Arkansas for the memorial’s dedication.

“Bring it to the light so that history is known, but bring it to the light that there’s a community that’s still hurting in Elaine, Arkansas," Walker said. “It’s as though a curse is still on that county. There’s a lot of poverty. It’s kind of a feeling of oppression still lingering in the air. You just shake your head and say: Is this America?”

Regarding interpersonal reconciliation on the issue of race, Sheila Walker encourages it, but warns that nobody should expect that it will be quick and easy.

“The conversations are difficult. And I’m not speaking about Chester because it’s never been difficult between Chester and I. It’s difficult with white Americans because they’re afraid of being attacked. Not listening to the story. If there’s truly to be a conversation you just have to listen. Whites have to listen and not put their emotions into it where they’re feeling that they’re being attacked, versus 'I’m going to listen because this is something that maybe I can learn from.'”

J. Chester Johnson discussed his new book Sunday, June 14 in an online event called "Damaged Heritage: A Conversation". Johnson was joined by Dr. Catherine Meeks of the Absalom Jones Episcopal Center for Racial Healing.

May 18, 2020

A Video Presentation to The Carter Center by J. Chester Johnson on His Latest Book, Damaged Heritage

On Tuesday, May 5th, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story Of Reconciliation (publisher: Pegasus; distributed by Simon & Schuster) was released. There has been considerable demand for J. Chester Johnson to present and discuss in-person his new book at major venues, such as The Carter Center, The National Cathedral, Trinity Wall Street, The Harvard Coop, and The Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing, among other locations. However, as COVID 19 began to take its inevitable toll, it was not possible for Mr. Johnson to appear in-person. Alternatively, he has been presenting at locations through Zoom or WebEx. For example, Trinity Wall Street produced the attached video for The Carter Center, which was recently posted on May 12th by The Carter Center for its clientele – the date originally scheduled for Johnson’s appearance. A number of similar video presentations by Johnson on Damaged Heritage are planned in various venues for the future.

January 12, 2020

The Elaine Race Massacre and the Elaine Race Memorial – Then and Now

Many of you are aware of the Elaine Race Massacre of 1919, and many of you aren’t. The Elaine Race Massacre of black sharecroppers and family members on the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River Delta may be the most significant attack against African-Americans in our country’s history with more than a hundred (and possibly hundreds of) blacks perishing.

On September 29th, 2019, the Elaine Massacre Memorial was dedicated in Phillips County, Arkansas, site of the conflagration; no permanent memorial to the event had previously existed. A series of pieces related to the Memorial in the form of links and attachments are set forth right below the following short description of the Massacre and its important aftermath.

Highlights of the Massacre and Aftermath:

During the Red Summer of 1919 when racial conflict between black and white Americans flared throughout the country, the Elaine Race Massacre stands out as one of the most brutal and extensive racial conflagrations. From early Wednesday morning, October 1st, 1919 into the following weekend, many African-American sharecroppers and family members were murdered. Five whites also died, although two may have been killed by friendly fire.

While whites feared a black insurrection where blacks outnumbered whites by multiples, they also feared the local black sharecroppers’ desire to unionize for improving economic negotiating power; these two factors contributed to the whites’ devastating aggression against the blacks. The largest number of deaths to African-Americans were caused by white federal troops with machine guns, brought into Phillips County allegedly to stop the black revolt. No investigation ever found that local African-Americans planned or executed an insurrection.

At the end of the killing spree in Phillips County by local whites, by white vigilantes from neighboring communities and states, and by the federal military, whites then relied on the torturing of black witnesses to evince the right responses supportive of an untrue proposition that a broad-based black rebellion had existed, which would be the only theory heard in the local courts at that time. No whites were charged, while seventy-four sharecroppers were found guilty of crimes ranging from first-degree murder to “night riding”. All-white juries often deliberated for no more than two minutes in finding blacks guilty.

Out of the Massacre and associated local court proceedings emerged a case, Moore v. Dempsey, that made its way to the U. S. Supreme Court, which found in 1923, in an opinion written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, that federal courts could overturn local and state criminal court proceedings which were unfair. This judgment by the U. S. Supreme Court put teeth in the 14th Amendment (equal protection under the law) for the first time since its enactment in 1868.

A significant brick in the Civil Rights road had been put in place. For his legal strategy that led both to the U. S. Supreme Court decision and to freedom after five years for all seventy-four sharecroppers found guilty following the Massacre, the black Little Rock attorney, Scipio Africanus Jones, will someday be recognized for the American hero he is.

___________________________________

I would like to share the following pieces. The dedication of the Elaine Massacre Memorial was held on the afternoon of September 29th, 2019, one day in advance of the Massacre’s centennial. While many people locally and beyond participated, David P. Solomon and the Solomon family, long-time residents of Phillips County, Arkansas, led efforts that resulted in the creation of the Memorial.

1. Video of the Elaine Race Massacre Dedication, September 29, 2019

2. Pictures of the Elaine Massacre Memorial

Photos by David Gruol

3. NPR "Here and Now" Interview: Aired on September 12, 2019, Robin Young of "Here and Now" interviews Dr. Kyle Miller and me. Dr. Miller lost four ancestors in the Massacre, and my maternal grandfather participated in the conflagration.

4. Two Articles of Interest (combined in one document): "In a Small Arkansas Town, Echoes of a Century-Old Massacre," The New York Times, July 25 2019, and "Arkansas Group Planned Monument to Racial Unity; It Isn't Going as Planned," The Wall Street Journal, September 14, 2019.

5. Memento Poem Card: An original poem composed for the Memorial dedication.

_______________________________________

In May, 2020, a new non-fiction book, DAMAGED HERITAGE: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation, will be published by Pegasus Books. A meaningful part of this book, which I wrote, consists of the journey, over the last six years, that Sheila L. Walker, who authored the Foreword, and I have shared to achieve racial reconciliation and authentic friendship in which our respective spouses and families have become an integral part. Sheila had family members victimized during the Massacre, and my grandfather participated in the conflagration.

For the book, the Massacre serves as a backdrop for my commentaries on race, racism, and reconciliation; in particular, the book discusses the reasons that racism repeats itself in this country from generation to generation, including the roles that both white damaged heritage and white filiopietism have played in the repetitive adherence of America to racism over several centuries to the present. It also offers approaches, including the lessons learned through racial reconciliation by Sheila and me, to end the vicious, dehumanizing (for both blacks and whites), and continuous racial subjugation. You may view the book cover below.

January 12, 2020

Review by Melinda Thomsen of Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems

Set forth below is a review written by Melinda Thomsen on Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems, which was published in 2017 by St. Johann Press. Johnson has said about this volume: “This is the closest piece of writing to an autobiography as I have ever written. The subject matter and timbre of the language represent issues that have occupied my art for the better part of my life.”

Set forth below is a review written by Melinda Thomsen on Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems, which was published in 2017 by St. Johann Press. Johnson has said about this volume: “This is the closest piece of writing to an autobiography as I have ever written. The subject matter and timbre of the language represent issues that have occupied my art for the better part of my life.”

Click the following link to read full review. Now_and_Then_Flier_final_w_revisions.ital_1-3-20.pdf

December 8, 2019

Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation - Coming May 2020

At the time J. Chester Johnson was writing the Litany of Offense and Apology for the national Day of Repentance (October 4, 2008) when the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils, he came across a seventy-page document, The Arkansas Race Riot, that had been written by the African-American historian and anti-lynching advocate, Ida B. Wells. She described an event, which later would be known as the Elaine Race Massacre, a massacre of black sharecroppers and their family members that occurred in Phillips County, Arkansas along the Mississippi River Delta in early October, 1919 during the Red Summer, a name given by the black poet, James Weldon Johnson, to that summer soon after the close of World War I, when multiple racial conflicts broke out in various parts of the nation. Phillips County was located only one county removed from Johnson’s childhood home, but neither Johnson nor friends and classmates from his youth that he contacted had knowledge of the conflagration. Still, it may have been the most significant racial massacre in our country’s history. Moreover, the judicial case, Moore v. Dempsey, which evolved in the aftermath of the violence, was decided on behalf of certain of the black sharecroppers by the U. S. Supreme Court, with Oliver Wendell Holmes writing the majority opinion, and became a landmark precedent that put federal support, for the very first time, behind the 14th Amendment (equal protection under the law) to the U. S. Constitution.

At the time J. Chester Johnson was writing the Litany of Offense and Apology for the national Day of Repentance (October 4, 2008) when the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils, he came across a seventy-page document, The Arkansas Race Riot, that had been written by the African-American historian and anti-lynching advocate, Ida B. Wells. She described an event, which later would be known as the Elaine Race Massacre, a massacre of black sharecroppers and their family members that occurred in Phillips County, Arkansas along the Mississippi River Delta in early October, 1919 during the Red Summer, a name given by the black poet, James Weldon Johnson, to that summer soon after the close of World War I, when multiple racial conflicts broke out in various parts of the nation. Phillips County was located only one county removed from Johnson’s childhood home, but neither Johnson nor friends and classmates from his youth that he contacted had knowledge of the conflagration. Still, it may have been the most significant racial massacre in our country’s history. Moreover, the judicial case, Moore v. Dempsey, which evolved in the aftermath of the violence, was decided on behalf of certain of the black sharecroppers by the U. S. Supreme Court, with Oliver Wendell Holmes writing the majority opinion, and became a landmark precedent that put federal support, for the very first time, behind the 14th Amendment (equal protection under the law) to the U. S. Constitution.

Johnson was challenged to learn as much about the event as he could. Ironically, during the course of the research and based on recall of family stories, he discerned that his own beloved maternal grandfather, Lonnie Birch, who was Johnson’s principal caretaker during the early years of his life, had actually participated in the Elaine Race Massacre. Five years after he first read the document by Ida B. Wells, Johnson wrote a serialized, four-part article entitled “Evanescence: The Elaine Race Massacre” that was distributed by the well-respected literary journal, Green Mountains Review. As a result of the article, he and Sheila L. Walker, a descendant of an African-American family victimized during the Massacre, became acquainted and soon thereafter committed themselves to a journey of reconciliation, which blossomed into a close friendship in which both of their respective families were part.

In addition to the above commentary, Damaged Heritage tells how one man’s journey through a history, a region, and a family of virulent racism ends remarkably in racial reconciliation. The book also argues persuasively that white racism against African-Americans will not end in this country until whites acknowledge and repudiate both “damaged heritage” and filiopietism, the partner in the historical crime of black subjugation. While the book describes, by real life experiences and personal history, why the country still suffers from white racism against black Americans, it also answers the question: how does one grow up in a racist society and not be a racist?

At a time when the election of Donald J. Trump ripped open the wound of America’s racism against persons of color, this book gives the country a set of insights and approaches that can put us on a path of reconciliation and devotion to the genuinely human that are essential for a nation to be at peace with itself.

For a hundred years, there was no permanent memorial to the Elaine Race Massacre. J. Chester Johnson served as co-chair for the Elaine Massacre Memorial Foundation, and on September 29th, 2019, a Memorial, located directly in front of the Phillips County Courthouse and some three hundred yards from the Mississippi River, was dedicated and opened to the public. As part of the Memorial ceremony, Johnson read an original poem he composed for the dedication. Here is the final stanza of the poem:

“Of time and the river,

Beckoning no escape,

Leaves no choice:

So, we shall no longer wait

For more light that we may

Better see light, nor wait

For other dreams that we

May better inspire dreams.”

J. Chester Johnson

is a well-known poet, essayist, and translator, who grew up one county removed from the Elaine Race Massacre site in southeast Arkansas along the Mississippi River Delta. He has written extensively on race and civil rights, composing the Litany for the national Day of Repentance (October 4, 2008) when the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils. At the height of the Civil Rights Movement and following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr, Johnson returned to the town of his youth to teach in the all African-American public school before integration of the local education system. Several of his writings are part of the J. Chester Johnson Collection in the Civil Rights Archives at Queens College, the alma mater for Andrew Goodman, one of three martyrs murdered by white supremacists in Mississippi during Freedom Summer. His three most recent books are St. Paul’s Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems (2010), Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems (2017), and Auden, the Psalms, and Me (2017), the story of the retranslation of the psalms in the Book of Common Prayer for which W. H. Auden (1968-1971) and Johnson (1971-1979) were the poets on the drafting committee; published in 1979, this version of the psalms became a standard. The manuscript, Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of Reconciliation, will be published on May 5, 2020 by Pegasus Books. Johnson, who served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U. S. Treasury Department, owned and ran, for several decades, an independent financial consulting firm that advised states, large public authorities, and non-profit organizations on capital financing and debt management. His poem about the iconic St. Paul’s Chapel, relief center for the recovery workers at Ground Zero, has been the Chapel’s memento card since soon after the 9/11 terrorists’ attacks (1.5 million cards distributed); American Book Review recently said of the poem: “Johnson’s ‘St. Paul’s Chapel’ is one of the most widely distributed, lauded, and translated poems of the current century”. One of fifteen writers selected to be showcased in October, 2019 for the first Harvard Alumni Authors’ Book Fair, he was educated at Harvard College and the University of Arkansas (Distinguished Alumnus Award, 2010).

Copyright © 2019 by J. Chester Johnson

October 6, 2019

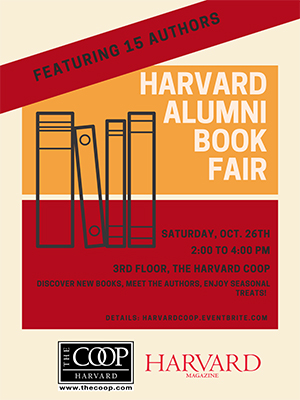

Event: Harvard Alumni Authors at the Harvard Coop October 26, 2019

On Saturday, October 26th from 2:00 pm to 4:00 pm, The Harvard Coop was transformed into a reader's delight at this inaugural Harvard Alumni Author book event, co-sponsored by The Harvard Coop & Harvard Magazine.

On Saturday, October 26th from 2:00 pm to 4:00 pm, The Harvard Coop was transformed into a reader's delight at this inaugural Harvard Alumni Author book event, co-sponsored by The Harvard Coop & Harvard Magazine.

ALL members of the Cambridge and Greater Boston community were invited to come meet the 15 authors, including J. Chester Johnson, browse to their heart's content, and buy books. Free snacks, and other special offers for attendees were included!

Biographers, critics, historians, journalists, memoirists, novelists, playwrights, and poets.....Harvard alumni have published diverse works across all literary genres.

This was a FREE event.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

I sold and personally signed my three most recent books: St. Paul’s Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems (2010); Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems (2017); and Auden, the Psalms, and Me (2017). I also shared information about my forthcoming book to be released in May, 2020, published by Pegasus Books: Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre And A Story of Reconciliation.

I sold and personally signed my three most recent books: St. Paul’s Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems (2010); Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems (2017); and Auden, the Psalms, and Me (2017). I also shared information about my forthcoming book to be released in May, 2020, published by Pegasus Books: Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre And A Story of Reconciliation.

Thank you for coming.

J. Chester Johnson

September 16, 2019

Interview by NPR of J. Chester Johnson and Kyle Miller on the Elaine Race Massacre and Memorial

Remembering The Elaine Massacre In Arkansas 100 Years Later

To listen to the interview, click here.

In what’s known as the “Red Summer of 1919,” hundreds of African Americans died at the hands of white mobs, from Chicago to Texas to South Carolina.

In Elaine, Arkansas, white mobs in the Elaine Massacre caused some of the most blood spilled. Death estimates run from 100 to hundreds of murdered black residents, the largest number in the “Red Summer.”

To mark the 100th anniversary, a memorial to the victims is set to be unveiled in Elaine.

Here & Now’s Robin Young talked to Chester Johnson, a white man who co-chairs the Elaine Massacre Memorial Committee and believes his grandfather took part in the massacre.

Johnson says the purpose of the memorial is to “raise an awareness [and] to also lead toward a level of reconciliation coming out of that awareness.”

Memorials and reparations for the victims’ families are “just one piece of the puzzle,” says Kyle Miller, the director of the Delta Cultural Center in Helena, Arkansas.

Miller lost some of his ancestors during the massacre — four young black men who were ripped off a train and killed.

He says the massacre significantly shaped his family, even causing one of his aunts to leave Elaine and never return.

To read the full article or listen to the audio, click here.

July 29, 2019

In a Small Arkansas Town, Echoes of a Century-Old Massacre

In this June 15, 2019, photo, a man works near a monument under construction honoring victims of the Elaine Massacre that sits across from the Phillips County courthouse in Helena, Ark. The Elaine Massacre Memorial is set to be unveiled in September.

ELAINE, Ark. (AP) — J. Chester Johnson never heard about the mass killing of black people in Elaine, a couple hours away from where he grew up in Arkansas. Nobody talked about it, teachers didn’t mention it in history classes, and only the elderly remembered the bloodshed of 1919.

He was an adult when he found out about it. By then, his grandfather, Alonzo “Lonnie” Birch, was dead — perhaps taking a secret to his grave.

Johnson believes Birch took part in the Elaine massacre. And now he’s bent on telling the story of one of the largest racial mass killings in U.S. history, an infamous chapter in the “Red Summer” riots that spread in cities and towns across the nation.

“I feel an obligation,” said Johnson, who is white. “It’s hard to grow up in a severely segregated environment and for it not to affect you. If you don’t face it and deal with it in various ways, it becomes undiscovered.”

___

EDITOR’S NOTE: Hundreds of African Americans died at the hands of white mob violence during “Red Summer” but little is widely known about this spate of violence a century later. As part of its coverage of the 100th anniversary of Red Summer, AP will take a multiplatform look at the attacks and the communities where they occurred. https://www.apnews.com/RedSummer

___

Johnson, who now lives in New York City, is co-chair of a committee overseeing construction of a memorial honoring those killed in 1919. He and others are hoping the structure, being built in a park across from the Phillips County Courthouse about a half-hour drive from Elaine, will bring attention to the massacre. Others say plans for a monument are a folly — starting with its location — and want commemoration efforts to focus instead on reparations to account for what they say was theft of black-owned land in the wake of the killings.

“It was literally a war on this area. People wanted the property that was almost all black-owned,” said Mary Olson, who is white. She is president of the Elaine Legacy Center, a red-brick community center that works to preserve the area’s civil rights history. It bears the sign, “Motherland of Civil Rights.”

The violence unfolded on the evening of Sept. 30, 1919, as black sharecroppers had gathered at a small church in Hoop Spur, an unincorporated area about 2½ miles north of Elaine. The sharecroppers, wanting to be paid better and treated more fairly, were meeting with union organizers when a deputy sheriff and a railroad security officer — both white — arrived.

Fighting and gunfire erupted, though it’s still not clear who shot first. The security officer was killed and the deputy wounded.

White men frustrated that the sharecroppers were organizing went on a rampage. Over several days, mobs from the surrounding area and neighboring states killed men, women and children.

More than 200 black men, women and children were killed, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery, Alabama-based nonprofit that has documented more than 4,400 lynchings of black people in the U.S. between 1877 and 1950. Five white people were killed. Hundreds of black people were arrested and jailed, many of them tortured into giving incriminating testimony. Some were forced to flee Arkansas and, according to the Legacy Center, had their land stolen.

Johnson said his grandfather, Alonzo “Lonnie” Birch, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and worked for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, the same company that employed the railroad security officer who was killed at the Arkansas church where the black sharecroppers had gathered to organize. Once the violence started, Johnson said, railroad officials urged workers to join the fighting. He said his grandfather likely responded to the call.

Narratives about the killings differ and records are not easy to find, said Brian Mitchell, an assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock. “You have to understand that everybody that had some degree of power in the state was a part of the process of the massacre, so the people who would control all the records are actively suppressing the records,” Mitchell said.

Some residents think the death toll is highly exaggerated.

Poindexter Fiser, the mayor of Elaine from 1985 to 2007, said the accounts of a massacre are “somebody trying to make something out of nothing much to talk about.” Fiser, who is white, said his late father-in-law put the number of those slain at only “about 25 people.”

Kyle Miller, director of the Delta Cultural Center in Helena-West Helena, Arkansas, said for many years, the violence “was not really acknowledged ... it was something that was only talked about behind closed doors.” Miller is a descendant of the Johnston brothers, four wealthy, black siblings who he said were pulled off a train on their way back to Helena after a hunting trip and killed during the massacre.

“I’m really hoping (the memorial) is going to spark some conversations. That people will look at it and begin to ask questions and be able to learn some history of our community,” Miller said.

The memorial is set to be unveiled in September.

Not everyone supports it. Members of the Legacy Center say the monument belongs in Elaine.

“If you said ’1919,′ what do you think of? Elaine,” said James White, director of the Legacy Center. “You don’t think of Helena.”

White and others with the center said any commemoration efforts should have some focus on the theft of black-owned land. Some residents are calling for descendants of the victims to receive compensation for what their families lost.

Miller and other memorial organizers say Elaine doesn’t have enough resources to sustain what they envision will become a civil rights tourist destination. And to them, the massacre story is bigger than Elaine: The Phillips County Courthouse in Helena was where hundreds of black men were jailed and tortured following the violence.

The effects of the violence and aftermath endure today. Elaine is still highly segregated: White residents live predominantly on the south side and black residents on the north side. About 60 percent of its 527 people are black.

“It’s a quiet town, but there’s still racial tension here because we’re still divided,” said White, a black Elaine native whose grandmother told him about black residents hiding in swamps to escape.

White said he welcomes efforts to learn about the massacre but questions who gets to tell the story and who benefits from sharing it.

“One hundred years later, it’s the same old game, just a different day,” he said, reflecting on the disparity between those that hold power in Phillips County and the poor black residents of Elaine. “It’s hate in this town ... and black people are still afraid” of talking about the massacre.

___

In this July 23, 2019, photo, poet and author J. Chester Johnson sits at his home in New York, as he talks about a 1919 massacre of African Americans in Elaine, Ark. Johnson believes his grandfather took part in the Elaine massacre, an infamous chapter in the “Red Summer” riots that spread in cities and towns across the nation. (AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews)

In this June 14, 2019, photo, residents participate in an Evangelical tent revival in a large field in Elaine, Ark. The effects of the violence during the summer of 1919 and aftermath endure today. Elaine is still highly segregated: White residents live predominantly on the south side and black residents on the north side. (AP Photo/Noreen Nasir)

May 7, 2019

J. Chester Johnson Spoke at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC on Sunday, June 30th, 2019.

J. Chester Johnson spoke at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC on Sunday, June 30th, 2019 at 1:00pm

J. Chester Johnson: Auden, The Psalms and Me

We welcome poet, essayist and translator J. Chester Johnson, who served from 1971-1979 as the poet on the drafting committee for the retranslation of the psalms, the version contained in the current Book of Common Prayer, published in 1979. The story of this retranslation, which will be the focus of his presentation at Washington National Cathedral, is told in Johnson’s book, Auden, the Psalms, and Me, published in 2017 by Church Publishing of the Episcopal Church. He replaced W. H. Auden, who served as the poet on the committee from 1968-1971.

These psalms have become a standard, illustrated by the fact that Lutherans in the United States and Canada, the Anglican Church of Canada, and the Scottish Episcopal Church have all adopted this American version of the psalms for their respective worship books and services; in addition, these psalms are approved for use by the Church of England and were adopted in England as the preferred translation for Celebrating Common Prayer, the pioneer in reforming the structure and style of the Daily Office.

Other recent books by Johnson are St. Paul’s Chapel & Selected Shorter Poems (2010) and Now And Then: Selected Longer Poems (2017). He has also written extensively on race and civil rights, composing the Litany for the national Day of Repentance (October 4, 2008) when the Episcopal Church formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils. Johnson just completed Damaged Heritage: From The Elaine Race Massacre To Reconciliation, a memoir and commentary on racial enlightenment and racial reconciliation; his agent is now approaching publishers with the book.

The National Cathedral, Washington DC

RECENT POSTS

DAMAGED HERITAGE and J. Chester Johnson on Times Square Jumbotron Dec. 21st

Damaged Heritage by J. Chester Johnson Selected for Library of Congress Shop

Damaged Heritage by J. Chester Johnson: Anti-Racism Text at St. Luke in the Fields

J. Chester Johnson's "Night" Featured by Carnegie Hill Village

J. Chester Johnson Named To Board of Advisors For Poetry Outreach Center

Conversation Among Descendants of the Elaine Race Massacre 104 Years Later: Zoom Recording Available

J. Chester Johnson Interviewed by Tavis Smiley

Cornelius Eady's Interview of J. Chester Johnson for Poets House/WBAI "Open House" Program

NPR Article on Elaine and Tulsa Race Massacres

Favorable Review of "Damaged Heritage" in Current Issue of American Book Review

Damaged Heritage Placed On Selective Goodreads’ List of Best Nonfiction Books

Damaged Heritage Motivates Nationwide Talks on Social Justice and Racial Equity

J. Chester Johnson Writes in the ARKANSAS TIMES About Another Arkansas Race Massacre

ARCHIVES

December 2024

October 2024

April 2024

March 2024

October 2023

August 2023

April 2023

January 2023

December 2022

September 2022

April 2022

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

March 2021

December 2020

October 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

January 2020

December 2019

October 2019

September 2019